‘The Dragon of Michelham Priory’, by E.E. Rhodes

My grandfather said to watch out for the dragon, in case he nabbed me, but I, being six, was more concerned with the moat.

The dragon was a dusty yellow, clacking monster, dancing along with a Morris troupe of red-faced labouring men. The moat, though, was placid, wide and dark, green and still.

Certainly there were cheerful ducks, in pairs and with half-grown ducklings, as well as coots, and shyer moorhens. But they all seemed to paddle hastily across the water, just to get where they were going and nothing more.

My grandfather held my hand tightly as we went under the medieval Gate House, over the bridge.

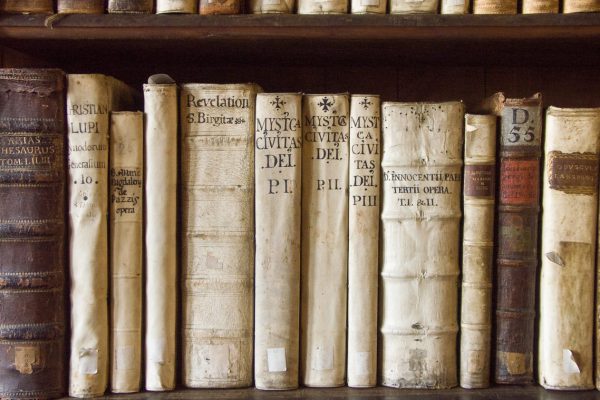

Inside the main house, it was both staired and gothic-arched in stone, and all the furniture smelled like beeswaxed effort. When I leaned on the panelling, after the long climb, I tried not to leave telltale tiny fingerpints.

The muted tapestries relieved the lime-white walls and in the Prior’s Chambers we came across a chair for a dragon. My grandfather sat in it, though I’m not sure he should. Maybe the staff were kind to him because he had a stick.

The leaflet about the Priory, smelling of fresh print and glossy like the polished wood, told us long, long lists of facts, but it was the friendly docent who mentioned the ghosts.

There were at least three, he said, including a Grey Lady in the Gate House, a Blue Lady in the Music Room, and a Wandering Monk in the Tudor Wing. Some of them had drowned, he nodded, with a little glee.

The dragon in the grounds was a Knucker, he said. It had come from a water hole and now lived in the Priory moat amongst the sodden ghosts, for better or for worse.

I shuddered at the thought of silvered weeds and long fingers under the water’s skin, dragging me down. I trembled at the idea of voices in my ears roaring at me to stay, so that the song of daylight and air and the earth above grew distant.

Maybe the ghosts were sirens, like the ones from faraway that we’d been told about at school, and they were lonely in their wearied haunts and hoping for company. My grandfather said the Gate House was a fine building and I wondered if it wouldn’t be so bad to be entangled there. It was so very green and wet and grey.

Later, blinking in the bright of the August sun, we each ate a vanilla cornet sold from an old fashioned ice-box. Already tired out, we sprawled across an unrolled tartan blanket on a bank of short mowed grass. Breathing a sigh of relief, we drank the flask of tea my grandfather had brought in his canvas rucksack. The cup had a comforting warm plastic smell and the flask was rich with tannin.

Across from us, on the close-cropped lawn, the Morris men danced on. The Knucker snapped at another child, snap, snap, and I knew that I would cry if he came near.

Stalls and displays were bright jewels round the grounds. My grandfather called it a bank holiday jolly. In my thoughtful, small child way I considered the general levity, and remembered the Augustinian monks which the docent had told us had traipsed across this lawn. I imagined them to be tonsured like the grass, and martyred.

We were good Catholics at home, though my grandfather was fiercely not. He said they’d been truculent and obdurate and Good King Henry had sacked the monasteries for a reason.

This was not the history that I’d been taught. But, sitting in the sunshine, with a cheese and tomato sandwich cut diagonally on soft white bread, anything seemed possible. So, I nodded to agree.

We looked at the stalls, bedecked with bunting and cheerful cloths, and watched a blacksmith at a hasty forge. He was a bit too much like the Knucker, with his yellow apron, and clacking grin. I was scared, even though he gave me a square head nail he had made. Tap, tap.

My grandfather bought me a small, decorated cross on a long leather thong. Perhaps he was not as fierce as I once thought. But he kept me away from the snapping Knucker. Both things a reward, I suppose, for being a good girl, mostly, and one who tried not to fuss.

The gardens were resplendent and quiet away from the gaggling throngs of costumed peoples. Each of the outdoor rooms was paved and gravelled and edged in summer beauty. A woman took a cutting with a pair of silver scissors, she looked around guiltily and carefully didn’t catch my eye.

She made her way up a path, the little scissors flashing in the sun. Snip, snip. Furtive glances were worse than anything for calling attention to yourself. I knew all the things that could give you away. No one stopped her, though, and when she left the garden she was smiling and patting her bulging pockets. My grandfather pursed his lips and said that some folks were simply rude.

When we got back to the bus stop we were both worn out, my grandfather from all his protestations, and I from the difficulty of being six in a time-mellowed house and sumptuous grounds you have not yet grown into.

Neither of us told my mother I fell in the moat.

Michelham Priory

Upper Dicker, East Sussex, BN27 3QS