‘The Composer’, by Ian Welland

Let me introduce myself to you. My name is George Verelain and I live in the grandest house in all of Buckinghamshire, a stunning Tudor Mansion called Chenies Manor. I lease the Manor from the Russell family and they allow me the courtesy of maintaining its finery and adding ostentatiously to its collection.

However, my story is not about me, but is about a composer. A composer who left his native France and travelled Europe in search of fame and fortune. A composer who considered himself finer than his contemporaries.

It all started during a visit to Venice in 1745. I was on a Grand Tour as part of my cultural education. One fine morning I took a stroll across the Rialto Bridge and stopping to pause at its central arch, I gazed down at the Gondolas bobbing on the canal. Suddenly, I heard raised voices and saw a man running toward me carrying manuscripts under his arm. I could not move out of his way and we collided.

Manuscripts scattered with one careering over into the canal. As it fell, the pursuing mob gave up and turned back from whence they came.

‘Apologies Monsieur, for I am so sorry to have collided with you,’ said the panting man.

‘No, Sir. The fault is all mine.’ I said, dusting myself off. I leaned down to assist the man to rise and gather himself. We decided to depart for Leno’s just off the bridge and over coffee, a tale unfolded.

‘My name is Chedeville. I am a composer and have been here in Italy for some years.’

‘Monsieur Chedeville, why were those gentlemen chasing you?’

Chedeville placed his cup back into the saucer. ‘They believe I stole from Vivaldi. Truth is, Vivaldi stole from me!’

‘Did you steal from Vivaldi?’ I asked.

‘Non, Monsieur. But, a Frenchman in Italy accused of stealing from an Italian, who would you believe?’

‘And, what exactly are you accused of Chedeville?’

‘I was with Vivaldi in Vienna. We were working together on a sonata for flute when I produced a series of sketches for my Opus 13. Vivaldi needed an allegro for his final concerto. Nothing was working for him. I was so protective of my work as he had stolen from me on several occasions but, in the interests of our friendship I allowed these indiscretions to pass by. The Opus 13 was very special to me and I was determined Vivaldi would not steal this one.’

‘Tell me more?’ I said encouragingly.

‘Vivaldi was unwell. He did not have long to live and was totally impoverished.

In comparison, I was financially secure and owed no debt. Vivaldi knew that if he finished his concerto, his widow would benefit following his death which would come soon enough. A final curtain call you might say?’

I quizzed Chedeville more. ‘He stole the Opus 13 allegro?’

‘One particular stormy evening, Vivaldi who had called upon his publisher to arrange a recital, headlined me to perform excerpts from my incomplete Opus. During my time at the Concert Hall, my apartment was entered and my allegro was stolen from my manuscript book. I knew instantly that my friend was at the heart of the matter.’

‘What happened then?’

‘I called on Vivaldi, but Signora Vivaldi was not allowing any visitors. The next day when I called, Vivaldi was dead.’

‘And the manuscript?’

‘Nowhere to be seen, Monsieur. Out of respect for his widow, I duly left the matter; indeed, a year passed with no sign of the manuscript or Vivaldi’s finished work. Then, last autumn, I received a letter from Bach saying he had visited Venice and the grand masters had decided on a benefit concert. Vivaldi himself had been born in Venice in 1678 and was their most famous son after Canaletto. Bach thought I should go to Venice as I had been one of Vivaldi’s closest confidants. I arrived in Venice just in time for the concert.’

Chedeville wiped his brow. I poured him some more coffee. ‘Please, do continue Chedeville.’

‘The first part of the concert was a selection of short pieces then after an interval, the orchestra played Les Quatre Saisons. It was a splendid performance and I was moved. However, the evening was not finished and there came an announcement. The orchestra had been given permission to play Vivaldi’s final concerto. My allegro segued the fourth movement and triumphant applause rebounded from the walls. In the wake of success, I was sad that my departed friend had once again shamefully stolen my work for his gain.’

‘I take it the men who were chasing you over the bridge were representatives of Vivaldi’s publisher?’

‘You are quite right, Monsieur. After many days of negotiation, I arranged an appointment to receive a settlement for my allegro. Upon arrival, I was handed a pouch containing a lesser sum and noticing the manuscript on top of a bookcase, I asked the publisher for water. As he left the room, I grabbed the manuscript and ran from the building.’

‘The manuscript, Chedeville! A manuscript fell from under your arm into the canal! Was it the one?’

Chedeville quickly turned to the small pile of sheets at his side. ‘It’s not here! Oh, my lord, my allegro! It’s gone!’

We quickly finished our refreshment and then headed back to the Bridge. There was no sign of the manuscript. It had been washed away by the choppy canal water.

I returned to England for Harvest and to the comforts of Chenies. The gardens basked with Autumn glow. The ghost, supposedly that of good Queen Bess walking the western wing after dusk, creaked as the candles in the parlour flickered in time to logs splitting in the fireplace.

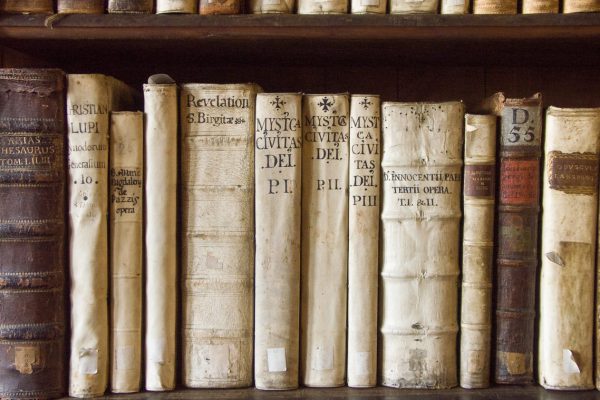

As winter took hold, I became confined to my library writing my diary and reading a book Chedeville had presented to me at our first meeting. In the following Spring, a letter arrived from Chedeville. The letter brought closure on the Vivaldi affair.

Dear Monsieur Verelain,

Forgive me, Monsieur, for I have not been honest. Yes, Vivaldi stole some of my sketches, though it was clear I was the one in awe and my jealousy had taken over. It was me who stole the allegro from him. I was struggling and my sponsor was pushing for a finished sonata for his wedding. The dying Vivaldi had no choice but to deny me his allegro. In my desperation, I stole the allegro. It is fitting that the manuscript should go to its watery grave in Venice.

I returned to Paris to complete my sonata and whilst on a visit to the Paris Observatory at the invitation of my dear friend Charles Messier, I chanced on a new idea for my allegro. Celebratory and yet, simplistic. I’m sure Vivaldi would have been proud of such a composition.

I have asked my publisher, Jean-Noel Marchand, to send you the original manuscript. Please ensure this is preserved for my creditors are sure to call-in my debts soon.

With you, the manuscript and my deception will lay; and I trust will remain at Chenies under watchful eyes of your descendants.

Your most humble servant,

Adieu,

Chedeville.

Chenies Manor House

Chenies, Buckinghamshire, WD3 6ER