Remembering Sussex’s Wild Past at Knepp Estate

Since 2001, the Knepp estate in Sussex has played host to the largest and most ambitious rewilding project in lowland Britain. Two decades in, the 3,500-acre landscape has been transformed by the introduction of free-roaming grazing animals and the spontaneous return of myriad native species, together helping to re-establish natural processes and allowing nature to flourish once more. Previously running the estate as a conventional dairy and arable farm, in 2000 owners Charlie Burrell and Isabella Tree sold their dairy herds and farm machinery, stopped using pesticides, fungicides and artificial fertilisers, and stepped back to allow nature to take its course.

Knepp has embraced a theory of grazing ecology which uses free-roaming grazing animals to restore soils and reshape the landscape, creating complex and rich habitats for a wide range of native fauna and flora. Whilst elk, aurochs (the primeval ox), tarpan (the original European horse), bison and wild boar would have roamed the wild plains and forests of Britain in prehistoric times, Knepp has introduced some more modern equivalents of these ancient species which follow similar grazing patterns. So far, these include three species of deer, old English longhorn cattle, Tamworth pigs and Exmoor ponies, a hardy ancient breed that are now an endangered species.

The estate dates back to the 12th century, and the original Knepp castle (now a ruin) was used as a hunting lodge at the heart of a thousand-acre Norman deer park. King John stayed at Knepp many times in the early 13th century, hunting deer and wild boar on horseback amongst the ancient oak trees. Over the centuries, the land was broken up for agricultural use, whilst other parts were landscaped to create a Reptonesque park and gardens for the new Knepp Castle, built by the architect John Nash.

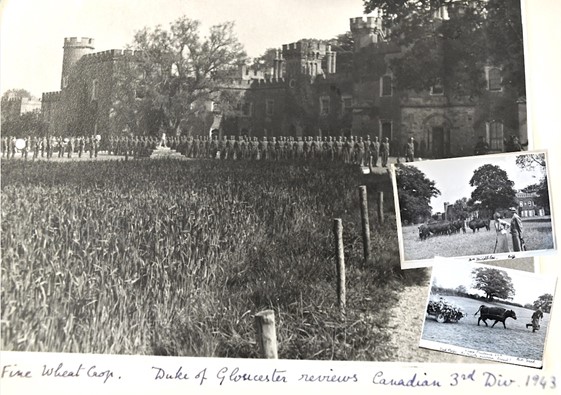

As part of the war effort, many of Britain’s historic estates including Knepp were requisitioned to station troops and house military hospitals, and their parks were repurposed to provide food crops. During this time, the Dig for Victory campaign transformed attitudes toward the land, with farming subsidies incentivising the intensive farming of every available patch of land. Landowners were even paid £60 (approximately £2200 in today’s money) for every veteran tree they felled to provide more land for agricultural use and provide timber for the war effort. In the post-war period, intensive farming practices became the norm, and it is only recently that agri-environment schemes have recognised the value of leaving more room for nature.

After centuries of human interference which dramatically changed the shape of the landscape, today Knepp Estate might begin to look more familiar to its Norman inhabitants of ages past. Red and fallow deer once again roam the ancient forests, and whilst Tamworth pigs have replaced wild boar, their knack for ‘rootling’ through soil has provided opportunities for wildflowers, shrubs, trees and insects to colonise the sward, in the same way their wild ancestors would have.

Knepp is also embarking on a regenerative farming project which will include the enhancement of flood plains, hedgerows and nature corridors within the agricultural land. Regenerative farming goes beyond standard sustainable farming practices by aiming to actively enhance the environment and regenerate the land, rather than simply reducing damage. A beef herd will be used to rotationally graze the land, allowing the soil and plants to rest and regrow in a practice known as ‘mob grazing’ which mimics the natural migration of herds of herbivores.

Toady, Knepp is a biodiverse sanctuary for all manner of species to call home, from all five native species of owl, Bechstein’s and barbastelle bats (the two rarest species in Europe), and the UK’s largest population of purple emperor butterflies. Recent years have also seen the welcome reappearance of hedgehogs, one of our most familiar but vulnerable mammal species, which had been missing from Knepp for more than two decades.

More endangered bird species turn up every year – such as cuckoos, whose numbers have declined catastrophically in the last century, and turtle doves, of which Knepp’s are the only growing population in the UK. Knepp recently had great success in their partnership with the White Stork Project, which aims to establish 30 breeding pairs of Storks in Britain by 2030. A symbol of rebirth, these majestic birds marked their triumphant return with two broods of chicks hatching at Knepp in May 2020, the first in Britain in over 600 years.

The estate is also involved in an ongoing project with Sussex Wildlife Trust to reintroduce beavers, an important keystone species, to the Sussex landscape. Before they were hunted to extinction in Britain in the 17th century, beavers played an important role in wetland ecosystems and flood mitigation in Britain’s lowlands.

Beavers are able to create vast networks of prime wetland habitat, which benefit a wide range of species including amphibians, fish and bats. Knepp is hoping to introduce a bonded pair of beavers to the estate in 2021, to begin to restore the 80% of Sussex’s wetlands that have been lost in the centuries since their departure.

Through forging such partnerships with conservation organisations, hosting visits from Natural England, the National Trust and the RSPB, and by working closely with policy makers, farmers and landowners, the rewilding project at Knepp has become a leading light for the future of British conservation.

Knepp’s dedicated team of environmental experts are also passionate about sharing the benefits of rewilding with wider audiences. As part of their mission, Knepp runs educational retreats and safaris to engage members of the public in their ongoing work, and share Knepp’s remarkable biodiversity with wildlife enthusiasts.

For Penny Green, resident ecologist at Knepp, the estate provides a vibrant reminder of the rich wildlife which would once have thrived across the English countryside.

‘A walk in the Knepp scrubland now is how I imagine a walk in the countryside might have been for my great-grandparents, amongst billowing hedgerows and messy field edges that would have been a haven for wildlife. To experience the sheer number of singing birds at Knepp transports me back a hundred years, and throws into sharp relief what we are missing in our wider countryside now that would have been so abundant then.’

‘In my lifetime, we have seen huge declines in much of our birdlife. More than a quarter of the UK’s bird species on the Red List now, with serious declines recorded in two species that are particularly close to my heart: the Turtle Dove has experienced a 98% decline in 48 years and the Nightingale a 92% decline. At Knepp, we have seen how nature can recover from a depleted landscape with these two species readily returning, and this return is bringing hope and joy to people.’

Ivan de Klee has worked with Knepp as a conservationist since conducting research on the remarkable recovery of turtle doves on the site. Like Penny, he values Knepp as a piece of England’s natural history come back to life.

‘When I started at Knepp, it felt like I was going back in time – into a missing childhood. The sound of the cuckoo suddenly hit me from when I last heard it at 8 years old, I realised that my friends and contemporaries were missing an entire part of our own history. To think back 100 years rather than 20, just makes you imagine – what an incredible wealth of nature there must have been.’

To see and hear the transformative work going on at Knepp for yourself, allow yourself to be transported to the wild landscape of West Sussex in the short film below. Charlie Burrell, Isabella Tree and their team share the highlights of the journey so far, with some beautiful images of the wildlife and habitats they care for.

By Lydia Gibson, with thanks to Charlie Burrell, Isabella Tree, Penny Green and Ivan de Klee for their contributions. All photos and videos courtesy of Knepp Estate.

You can read the full story behind the project in Wilding, by Isabella Tree (pub. Picador 2018). For more information about Knepp and their Safaris, visit their website here.