‘A Certain Pleasing Irony’, by Margaret Morey

Saturday lunchtime. Summer. The start of the sixties. My Dad’s home from his job at the steelworks in Middlesbrough. He only works a half-day on a Saturday. He goes upstairs for a good wash, and comes down in a suit and tie. We’re going to Stockton Show at Wynyard Hall, and he is wearing his Sunday best. We’ll be allowed to look inside the hall, and he’ll want to make a good impression, if we meet the marquis.

My Dad prides himself on being left-wing, but there’s a streak of deference, obsequiousness even, running through him. I know that if he were to meet the new Marquis of Londonderry this afternoon, he would embarrass me by doffing his trilby hat, and telling him how he’s a working man, and how the charge-hand’s an idiot. Luckily, I don’t think the marquis will be anywhere to be seen. I think he just tolerates having the show on his land because the estate which he has recently inherited, is so short of money. He’s only in his twenties, and, rumour has it, he has long hair and is usually seen in a pair of jeans and an open-necked shirt. I’ve heard him described as a hippy.

I’m doing well at the Grammar School, a bit too big for my boots, but confident enough in my political views not to kowtow to any marquis. We have to get the bus, because we don’t have a car. I’m relieved when the bus pulls away. At least we’re going this time. Last year, things went wrong and we never got to the show, but this year it looks as though we might make it. Last year, my best friend June was coming with us, and we were playing horses in the garden, as eleven-year-old girls used to do in those days. waiting for my parents to appear. When they eventually showed up, they looked ready, but it turned out that there was a last minute crisis. Our neighbour, Elsie, had some horrible degenerative disease, and she and her house were mucky. She’d piled old carpets beside her bin. The neighbourhood cats used these for a bed, and my mother said that when she went to the bin that afternoon, several fleas from Elsie’s old carpets leapt through the fence and onto her person. At this point, my Dad was sent to the chemist to get flea powder, with strict instructions not to tell the chemist it was for us. By the time my mother had fumigated herself and the house, it wasn’t worth going.

But this year, it’s looking good. Everyone streams off the bus, through the big golden gates. There are agricultural stalls in the vast grounds. A warm smell of manure speaks of summer in the countryside. Sheep and lambs bleat, cattle bellow, and horses’ hooves pound from the show-ring. But most exciting of all, we plebs are allowed inside the hall for a look around. I’d like to head straight for the show-jumping, but my Dad is desperate to get through that door into the hall. He’s been reading up on the history. There is a great sense of faded grandeur, even more faded than our little nineteen-thirties semi, and much more grand.

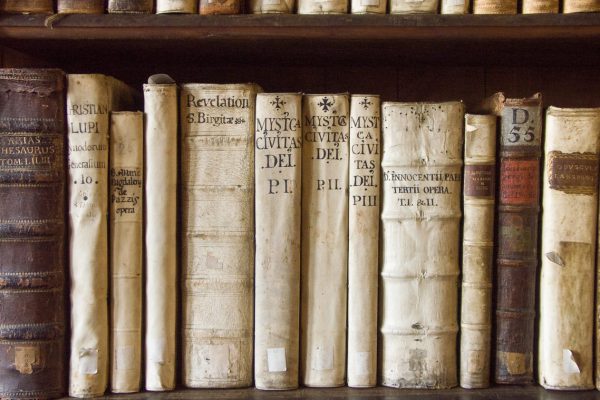

The entrance hall is enormous, with a staircase leading up from it. There is a rope across. We are not allowed upstairs. My Dad sniffs the air. There is a musty, mouldering smell. Such a sense of history he says. So many famous people have stayed here. He bends towards me in a confidential way. Including Edward the Eighth, the one who abdicated.

You mean the fascist? I ask as loudly as I dare. The one who signed a pact with Hitler? I’m being careful. I don’t want him to march us back to the bus, having got this far.

The old hall is dirty; the roof leaks; the grounds are overgrown. When we’re safely back home where no one can hear, my Dad sits on the hearth with his back to the fire, and delivers a mini lecture about how the money for the hall came from the Vane-Tempest coalfields on the Durham coast, and how this has dried up. There have been crippling death duties, he says. Only right and proper. That lot ever did a day’s work in their lives. Their money came from the exploitation of the working classes.

He lights his pipe and sucks it with righteous indignation.

***

Mid-morning. Summer. Nearly sixty years later. I’m on a huge luxury coach which is sailing through the entrance to Wynyard. Since 1987, the estate has belonged to John Hall the son of an Ashington miner who developed a passion for roseswhen his Dad gave him a bit of the family garden at the back of their pit-house. I’ve wanted to come back for a long time, to see the changes, to see what I can remember. The coach struggles down a narrow road with very executive houses, knocking leaves and branches from trees and hedgerows. Everyone’s gawping at the houses. They’re the most expensive and exclusive houses in the area. They certainly weren’t here in the sixties. And so many of them.

I’m embarrassed to be on the coach. I feel as though I’m arriving at a tiny Greek island on a massive cruise-liner which disgorges its passengers to overrun the place and plonk their large backsides in the only café, complaining about the heat. Coach trips and cruises aren’t my scene: I’m an independent traveller. But this is a Gardening Society trip. It’s convenient and sociable. And my circumstances have changed. Now I’m on my own, I have to take entertainment where I can find it.

We drive past the hall which is now a very exclusive hotel. From what I’ve seen on the website, it looks as though the interior has been restored to its former glory. I think of going back there, for a meal or a short stay. Another time.

Today, we’ve come to see the rose garden which John Hall, the new owner, has created. The society has had a talk from the gardener who designed it. It’s innovative. Not your average rose garden. There is a stunning collection of David Austen roses, but there’s herbaceous planting as well, and lots of hard-landscaping.

The sun’s warm. It’s a lifetime since I was last here. It’s gone in a flash. The hall’s changed, and so have I. So much has happened, and in a way so little. I’ve come full-circle in some ways. Alone again, but not the same person. The estate has been renovated to a high standard of indulgence and luxury. It’s having a second hey-day which, like the original one, will last as long as the money keeps coming in. I wonder what my Dad would feel about a miner’s son from Ashington owning this lot now. I think it has a certain pleasing irony…