Rome Is Where the Heart Is: The Story of Ushaw

In this article for Historic House magazine, author Elena Curti discovered an extraordinary Roman Catholic institution in County Durham; Ushaw Historic House, Chapels and Gardens.

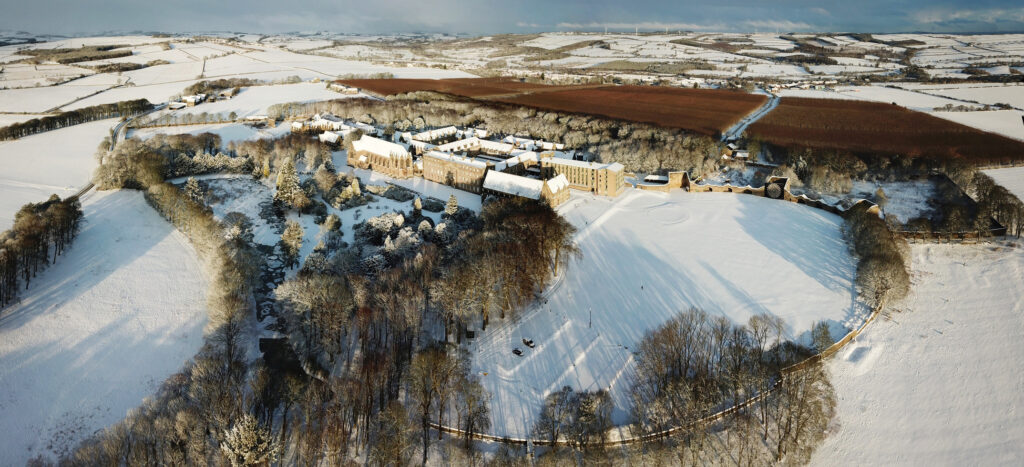

In the fading light of a freezing January evening, a plain Georgian house and massive Victorian Gothic buildings loomed into view: my first glimpse of Ushaw College, the great Catholic seminary for the north of England.

It was 2006 and I was a journalist at the Catholic weekly, The Tablet, covering a weekend conference. I remember the ride in the minibus from Durham Station. It was less than four miles to the college but, as we drove across windswept moorland whitened with frost, the city felt like a world away.

© Photography by Alex Ramsay. Copyright Patrimony Committee of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales

The northern bishops, who are Ushaw’s trustees, had been agonising over what to do about the seminary for years. On the one hand it was of unparalleled importance to Catholic history and culture, but on the other it had become impossibly expensive to run. Only around thirty men were training for the priesthood in buildings designed for ten times that number.

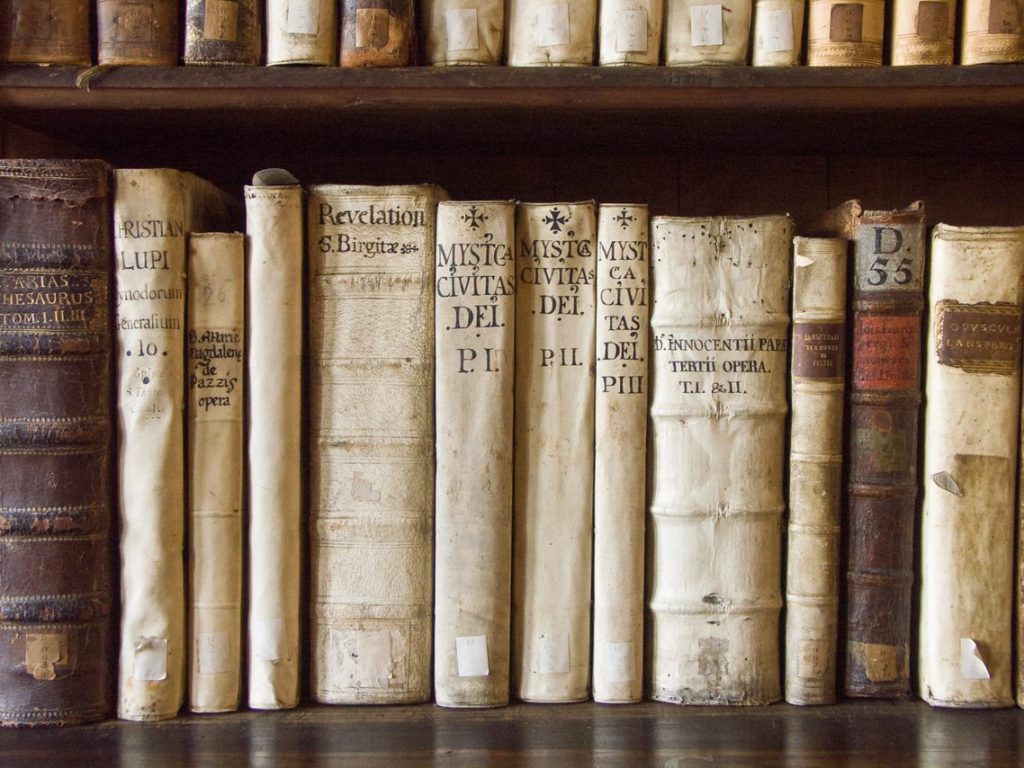

During the conference, the delegates brought chatter and cheer, but I thought of how gloomy and empty the place would be when they were gone. Everything spoke to past glories. The wide, draughty corridors were lined with cabinets displaying beautiful vestments, church plate and rare volumes. We queued for canteen meals in the enormous refectory lined with portraits of august cardinals and former presidents of the college.

© Photography by Alex Ramsay. Copyright Patrimony Committee of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales

One night we attended a service in the main chapel dedicated, like the college, to St Cuthbert, the saint credited with evangelising the North. The congregation sat facing one another in grand choir stalls while far away at the east end a huge, multi-spiked high altar reared up between stained glass, brass, tiles and milk-white marble statues glowing in the candlelight.

Next morning, going back to see St Cuthbert’s in daylight, I discovered a complex of smaller chapels tucked away off a vast vaulted corridor lined with the Stations of the Cross. I had never seen quite so many Gothic riches gathered in one place. I was in seventh heaven.

© Photography by Alex Ramsay. Copyright Patrimony Committee of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales

It was those chapels that eventually drew me back to Ushaw on a fine summer’s day in 2019. I was writing a book listing my favourite Catholic churches. By then, Ushaw had flung open its doors and was buzzing with activity. There were visitors wandering around the house, gardens and chapels. Others were attending exhibitions, a church history conference was underway, and the café was full of people enjoying coffee and cake. There were posters advertising summer activities for children and concerts.

This extraordinary transformation had begun in 2011, when the bishops finally decided to close their beloved seminary. Early plans to replace it with a Catholic cultural centre supported by Durham University hadn’t weren’t enough for the place to survive, but a future as a heritage attraction, inviting the general public in to admire its astonishing array of treasures, did seem viable.

© Photography by Alex Ramsay. Copyright Patrimony Committee of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales

Until then Ushaw had been one of the Catholic Church’s best-kept secrets, self-sufficient and self-contained. There were ‘Ushaw families’, whose members worked at the college for generations, but most locals had never crossed the threshold. One friend, Durham born and bred, told me she had never even heard of it, and there was just as little awareness nationally outside Roman Catholic circles.

The estate is huge: 200,000 square feet of buildings – almost all of them listed – in 550 acres. There are fourteen chapels, a magnificent library and precious collections of art, vestments, church plate and curios. In its heyday, Ushaw functioned like a small town with its own farm, dairy, bakery, gasworks, tailors’ shop and walled garden for fruit and vegetables.

The pioneer of the Gothic Revival, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin, produced some of his finest work here, added to by his son, Edward, other members of the Pugin dynasty, and Joseph Aloysius Hansom, now associated with the cab he invented but chiefly one of the finest architects of his day.

Ushaw’s story begins with the English Catholic seminary set up a Douai in the Spanish Netherlands during the reign of Elizabeth I. This college trained men for the priesthood and educated the sons of the Catholic gentry at a time when their faith was outlawed in England and Wales.

Douai’s founder, William Allen, a priest, later cardinal, from Lancaster and a former Oxford don, aimed to keep English Catholicism alive and to send missionary priests across the Channel. Douai was the key centre-in-exile of English Catholic resistance, producing more than a hundred martyrs and becoming a centre of learning to rival the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge.

© Photography by Alex Ramsay. Copyright Patrimony Committee of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales

The college thrived until the French Revolution, by which time Douai had become part of France. It was now much more dangerous for the staff and students to stay than to return to England, where hostility to Roman Catholics was fading. They established a seminary at Old Hall Green in Ware, Hertfordshire, but while students from the north and south of England had co-existed peacefully while abroad, tensions quickly emerged back on home soil. These crystallised around some high jinks in which a group of Lancastrian students dunked a southerner in a pond. They were severely reprimanded by their superior and in consequence walked out, demanding a seminary of their own.

Bishop William Gibson, Vicar Apostolic of the Northern District (1790-1821) and a former president of Douai, brought them to the North East and began fund-raising. They stayed in a succession of temporary homes until Gibson bought land at Ushaw and commissioned a simple Georgian house built around a central quadrangle.

Conditions were freezing and unsanitary for the first 52 men who moved in during 1808. The house was unfinished with many of the floors unflagged and windows unglazed. Five died in an outbreak of typhus and were buried in a woodland cemetery. The first college president, Thomas Eyre, joined them a year later.

The college followed the Douai tradition of functioning as both a boarding school educating boys and as a seminary training priests. Within decades of its completion the house was too small for the number of students.

© Photography by Alex Ramsay. Copyright Patrimony Committee of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales

The Catholic Church in England and Wales underwent momentous growth in the nineteenth century. The Catholic Emancipation Act (1829) legalised Catholic schools and poor Catholic migrants sought work in England, especially in the docks, mills, and factories of northern cities. Catholicism was resurgent after Pope Pius IX restored the Catholic hierarchy in 1850, creating dioceses with presiding bishops. John Henry Newman led a stream of Anglican converts to Catholicism. In a famous sermon of 1852, he spoke of a, ‘Second Spring,’ for the faith.

On the cusp of this transformation, Ushaw’s ‘second founder’ took charge. Monsignor Charles Newsham was educated at Ushaw and served as vice president, before being appointed president in 1837, remaining in post until his death in 1863. A portrait in the Refectory shows him, characteristically austere, in plain black robes in his bare-walled office holding architect’s drawings for his seminary. Newsham’s regime was characterised by ruthless efficiency, high academic standards and harsh discipline. He believed that splendid architecture and beautiful art (especially from Rome), would instil in his charges an appropriate sense of awe, and piety.

First, he appointed Augustus Pugin to build a bigger chapel dedicated to St Cuthbert. This, according to Eamon Duffy, Emeritus Professor of History of Christianity at Cambridge University, ‘was a small-scale but sumptuous jewel-box, which placed Ushaw at the forefront of the English Gothic Revival.’

Then Newsham appointed Joseph Hansom to transform the old chapel into a ‘public room’ known as the Exhibition Hall. Hansom designed a hammer-beam roof with images of the patron saints of the arts and sciences at the beam-ends. He added pointed arches to the windows and filled them with armorial glass bearing the arms of the presidents of Ushaw. Next, Hansom, with his brother Charles, built what became known as the Big Library, designing it to balance with Pugin’s chapel on the other side of the Georgian house.

The Hansom brothers built a model farm with state-of-the-art machinery and laid out formal gardens. They also built a unique Ushaw feature: enormous ‘bounds walls’ to the right of the main buildings used for ‘Cat’, a bat and ball game invented at Douai and still played by alumni at their annual reunion.

Pugin, meanwhile, had begun work on the series of small chapels clustered around St Cuthbert’s. But he was then heading towards his final catastrophic mental breakdown and died before completing his designs. The task fell to his eldest son, Edward, who finished St Joseph’s Chapel when he was just 17. Edward was also responsible for such gems as the chapel of St Charles Borromeo, patron saint of seminarians, and the Mortuary Chapel commissioned by the family of an Ushaw priest, the Revd Michael Gibson, as his mausoleum. The latter is an extraordinary vaulted space rich in stone decoration with a reredos depicting the Last Judgement, and the final resting place of Mgr Newsham.

Edward Pugin built or Gothicised many more buildings, his biggest commission being the prep school, Junior House, with its own chapel, refectory, and games area. This was closed in 1972 and has been mothballed ever since.

Newsham’s building programme and the accumulation of treasures left the college mired in debt. He had fought to keep Ushaw independent but his successor as president, Dr Robert Tate, fearing bankruptcy, ceded control to the northern bishops. Soon after, Ushaw benefited from a stroke of luck. Coal mined on the estate proved so plentiful that mineral rights were sold, clearing the debts and creating a reserve of capital.

Some of this helped to pay to rebuild Ushaw’s chapel in the 1880s. By this time Pugin’s building had become too small and was showing signs of instability at the east end. Work began under the architectural practice of Dunn and Hansom (successors to Joseph and Charles) of Newcastle. They dismantled Pugin’s chapel and replaced it with one twice the size, carefully incorporating as much as they could of Pugin’s stained glass and fittings.

This is the St Cuthbert’s Chapel that visitors see today. Much of Pugin’s original vision is intact, from the magnificent Paschal Candlestick – used for the Easter ceremonies – that stands ten feet tall with its candle, to the noble eagle lectern. Both were shown at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in the architect’s Medieval Court.

Pugin’s original high altar –more dignified and restrained than the overblown affair that replaced it – is in the antechapel. Recently restored, it glitters in red and gold, with low reliefs of Christ’s passion in six ornate niches in the reredos. Fund-raising has started for the refurbishment of the Lady Chapel close by, originally by Pugin but with fabulous polychrome decoration by J.F. Bentley, who went on to design Westminster Cathedral.

Ushaw has the biggest collection in England of art by the Nazarenes, a German Pre-Raphaelite-style group who were based in Rome. One member, Karl Hoffmann of Wisebaden, produced exquisite white marble statues of St Joseph and the Virgin Mary. One of these, Our Lady of Help (1851), is also known as Our Lady of Ushaw. The Madonna holds Jesus so that he faces the onlooker with arms outstretched. He is not an idealised figure or miniature adult but a real, chubby baby.

Five paintings by another acclaimed Nazarene, Franz von Rohden, can be seen at Ushaw. One, in the Oratory of the Holy Family, brings together the Adoration of the Shepherds and the Magi (1851), a devotional prototype that was to acquire iconic status. The painting was almost lost when the boat bringing it from Rome sank in the Mersey. Also rescued was a collection of eight hundred religious relics, many in elaborate baroque reliquaries, on display in the chapel. They are said to include relics of the True Cross and Crucifixion, hair of the Virgin Mary and fragments of bone from St Joseph, Mary Magdalen and John the Baptist.

Ushaw’s library and collections were carefully catalogued by a team from Durham University after the seminary’s closure. Among the most precious items are St Cuthbert’s Ring, made of solid gold with a large uncut sapphire, and a Book of Hours once owned by Richard III. The ring was taken from Cuthbert’s tomb in Durham Cathedral and for many years was venerated as a genuine relic of the saint. However, it has been dated to the thirteenth century and was probably donated by a wealthy medieval pilgrim.

Another treasure is the Westminster Vestment (1460-90), a red velvet embroidered chasuble believed to have been used at Westminster Abbey and also associated with Richard III. Vincent Nichols, Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, wore it when he celebrated a Requiem Mass for the last Plantagent king prior to his reburial in Leicester in 2015.

© Photography by Alex Ramsay. Copyright Patrimony Committee of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales

There are also many secular items, proof of the college’s determination to provide a fully rounded education. These include the Ushaw Orrery (1794), a clockwork scientific instrument used for demonstrating the Solar System. The makers were William and Samuel Jones of Holborn, whose customers included Thomas Jefferson and Harvard College.

The Big Library has many works of philosophy, science and natural history. These include Mark Catesby’s beautifully illustrated Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (1859), and a well-thumbed first edition of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), used to counter Darwin’s theory of evolution in public debates.

All these wonders have attracted growing visitor numbers, from just seven thousand in 2012 to around fifty thousand last year. Special events have been a huge success, and only days before lockdown Ushaw was preparing for an exhibition of 35 paintings by the internationally renowned artist Mark Fairnington, entitled Relics, juxtaposing hyper-realistic images from the natural world alongside items from Ushaw’s collections.

Lockdown of course put that on hold, but the months of closure have been spent planning for the ‘new normal’ as restrictions are relaxed. Emergency grants have helped, including £50,000 emergency funding from the National Lottery, on top of pre-virus funding to find uses for almost half the property that remains empty, including Edward Pugin’s junior seminary and the Hansoms’ model farm. Challenges remain, but Operations Director Peter Seed believes Ushaw has a distinct advantage for the next stage of re-opening.

‘The vastness of the buildings helps us greatly with social distancing,’ he says. ‘We have oceans of space: great wide corridors and enormous rooms. We can make our visitors feel completely safe and secure.’

Seed’s ancestors helped build Ushaw and he has spent his entire career there. The seminary’s closure was, ‘like a bereavement’ he says. That’s why he’s determined that the hard-won progress of the last few years is not lost. “We have come an awfully long way and we are not going to be beaten. We put so much into reviving this place, it would be a sinful waste to let it go now.’

Historic Houses members visit free

St Cuthbert’s Chapel features in Elena Curti’s book, 50 Catholic Churches in England and Wales to See Before You Die: and many more worth a detour. Read a review of it in the next issue of Historic House magazine.

For Alex Ramsay’s images:

‘Photography by Alex Ramsay. Copyright Patrimony Committee of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales.’

Ushaw: Historic House, Chapels and Gardens

Durham, DH7 7DW