Labours of Love: Middleton and Lamport Hall

Around fifty of Historic Houses’ one and a half thousand member properties are owned or run by independent charitable trusts. Middleton Hall in Warwickshire and Lamport Hall in Northamptonshire epitomise, respectively, the stories of rescue and bequest that lead houses to charitable ownership. James Probert went to find how much these ‘houses without owners’ really differ from each other and from those that are still lived in by their families.

The half-timbered building at Middleton Hall

Middleton Hall

Middleton Hall in north Warwickshire is a miraculous survival. A palimpsest of a building, it has been expanded or altered in every century since the late middle ages. From the fifteenth century until 1924 it was the seat of the Willoughby family, ennobled as the Barons Middleton in 1711 (and who now live at Birdsall House in Yorkshire).

By the eighteenth century the family lived primarily at yet another of their houses, Wollaton Hall in Nottinghamshire (also sold in 1924 and now a museum). Middleton was leased to tenants – including several with claims to fame in their own right. Sir Francis Lawley, the sixth Lord Middleton’s brother-in-law, was a local MP who occupied the hall in the first half of the nineteenth century. A keen agriculturalist, he is a contender for creator of the famous Tamworth pig breed.

If it wasn’t Sir Francis, it was his great friend and near neighbour at Drayton Manor (today a theme park), Sir Robert Peel, whose son of the same name became Prime Minister and established Britain’s first modern police force. The links between the two houses are still close; Sir Francis was succeeded as the tenant at Middleton by John Peel, a cousin of the Prime Minister, and today the Peel Society maintains its museum of police history in the west wing.

The estate was sold again, to a gravel firm, in 1966. The house was left unoccupied and fell into disrepair remarkably rapidly.

One of my volunteer guides hinted that the rate of decay may have been speeded up by deliberate actions of the gravel extractors, eager to demolish the Grade II* building in order to excavate the ground it stood on – we’ll probably never know the truth.

Only eleven years after it was last lived in the house was such a wreck that, when some history-buff ramblers asked the local authority about restoring it, the council’s survey concluded it was too far gone for rescue. Fortunately, others disagreed; an independent trust was formed and eventually a 75-year lease secured from the gravel company, along with a promise of annual funding for building materials (which lasted for ten years from 1980).

A step-by-step approach was taken to restoring, first, the garden and outbuildings and then, in turn, the wings of the main house ranged around a courtyard (now partially open on one side thanks to the 1920s owner, who demolished the fourteenth-century chapel – apparently in order to get his beloved cars inside).

The classicised Tudor great hall and largely Georgian west wing were stabilised and pressed back into use as event spaces (generating much-needed extra revenue for the trust) by volunteers and labour from the Manpower Services Commission. The opposite range, the most recent major renovation project, includes the fine thirteenth-century Stone Building, probably the oldest surviving domestic architecture in the county, and the half-timbered John Ray Building, named for a pioneering naturalist and ornithologist brought to the hall by polymath Francis Willughby (sic), his former pupil.

Together Ray and Willughby set out, as members of the Royal Society in the 1660s, to classify the entire organic world, working abroad and at Middleton; their system anticipated Linnaeus’s by some fifty years. No doubt they would find it appropriate that the surrounding gravel pits that for so long threatened the house are now a water-filled RSPB reserve.

Lamport Hall

It was another early member of the Royal Society, Sir Justinian Isham, who built the central block of Lamport Hall, my second destination. His family had built their first house there in the 1560s and for generations were pillars of the local gentry, but by the twentieth century familiar storm clouds were gathering.

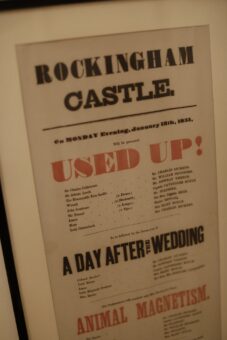

Sir Charles, the 10th baronet who lived at Lamport from 1846 to 1903, was a keen gardener; he’s credited with introducing the first garden gnome into Britain from Germany. (The little chap is on display in the house today, behind glass and widely reported as being valued at over £1 million). Sir Charles faced the ‘Downton Abbey’ problem of having only daughters but an entailed estate: the heir to his title, his first cousin once removed, would also inherit the house and land.

His response was to mortgage his property up the hilt in order to provide dowries for his children to marry well (which they did, including to the owners of Dunvegan Castle and Longnor Hall). When Sir Vere, 11th baronet, arrived to take up the reins he found his inheritance so encumbered he couldn’t afford to live in his new house. It was let to tenants for a while, became a country club for a short time, and eventually housed British and Free Czech soldiers and Italian prisoners of war.

All that took its toll. Sir Gyles Isham, who at various times in a glittering career was President of the Oxford Union, a lieutenant colonel in the King’s Rifles, an intelligence –officer in mandate Palestine, an elected local politician, a genealogist and historian, and a Hollywood matinee idol, inherited in 1941, while fighting Rommel in the desert.

On his return home from service in -1947 he found an estate that had already been neglected and decaying for half a century. He never married or had children, and the heir to the title was an unknown third cousin once removed, farming in Argentina. Even as he set about remedial works with great energy, he must have feared for the long-term future of the house he loved.

By the 1970s he had opened up some of the building to the public (though only the ground floor was safe for visitors, leading the attraction to be nicknamed ‘Northamptonshire’s stately bungalow’).

In 1974 he placed the house, parkland and remarkable contents (which include an outstanding collection of art and furniture acquired by the 3rd baronet during his Grand Tour in the 1670s) into a preservation trust. On his death two years later he left the remainder of the estate to a separate trust designed to provide income for the hall.

Despite his careful planning, arguments ensued, and the property spent ten years in legal limbo. The farms, the basis of the Trust’s core income today, remained -in part, but by the mid-1980s there was no cash left, and fragmented management during the ‘ownerless’ years of executorship meant little progress had been made on Sir Gyles’ project of restoration.

The story of the house since then is largely the story of one man’s will and vision. George Drye, a former National Park manager, was hired as Executive Director of the two trusts as soon as Sir Gyles’ bequests were free of the executorship, tasked with bringing together management of the neglected agricultural estate, consolidation and restoration of the hall and gardens, conservation of its priceless contents, and administration of the house as a tourist attraction and a place of practical learning (the trust’s charitable objects include education as well as preservation of the building).

‘Not many have that sort of career background,’ he says. ‘That’s four jobs, not one!’ I point out that there is probably only one cadre of people in the country who do regularly carry out all those roles – the owner-members of Historic Houses. Sitting at his desk in a book-lined study overlooking the grounds, in a part of the house in which he also lives, telling us about his 35-year stint in charge, beneath a portrait of his ‘predecessor’, Sir Gyles, he is every inch the country house custodian, and would be hard to distinguish from many a family scion now in charge at the neighbouring ‘big houses’.

‘We don’t want to be a museum,’ he says. ‘We want to retain the feel of a lived-in house. And that goes down well with the insurers – if the fire alarm goes off in the middle of the night, someone’s here to respond.’

Like Middleton’s trustees, George has gone slowly but carefully with the work at Lamport, funding it from the estate’s own resources – there is no grant money here. Before making his own settlement Sir Gyles had offered the house to the National Trust, who turned it down because of its poor state. ‘He dealt with extensive dry rot, the biggest structural issue, in his own lifetime – by taking half the house apart and treating it,’ says George, ‘but he never got round to putting it back together again.’ George’s sees his role as the seamless continuation of the work started by the trust’s far-sighted benefactor.

Not that George would ever allow himself to supplant the family that created all that he now cares for. ‘Relations with the Ishams were very strained when I arrived,’ he explains. ‘They felt they’d been disinherited. But everything Sir Gyles did was right – with inheritance tax where it was in 1976 the place would have had to have been broken up and sold off, along with the paintings. Now, I’m happy to say, I have a very good working relationship with the current heir to the baronetcy, Richard Isham – in fact he recently became the chairman of the board of trustees.’

George is retiring this year, after the best part of a lifetime overseeing a restoration that is now virtually complete, and his are big shoes to fill. Handover to the ‘next generation’ is as important here as in a family house, and in his remaining months George is working closely with the new appointee, a young man coming from the Church Commissioners, whom the trustees hope will stay, as George did, for a long term.

Allowing himself a last wistful glance from an upstairs window across the immaculate parkland, he says of his replacement, ‘You’ve got to grow up with the job – no one is just going to slot into this kind of role from day one.’

At Middleton Hall too, change is in the air. There are still a couple of physical projects in the offing – the stunning but dilapidated Tudor barn will soon become an education space – but it’s clear that the building’s story is entering a new chapter. A joint grant from the National Lottery and the Architectural Heritage Fund – the first major external money the trust has received – has enabled work on a masterplan to review every aspect of the site’s use.

‘It’s highlighted that we’re a very mindful location, so for example we could do tai chi, yoga, all sorts of things to help people,’ Amy Evans, Visitor Experience Manager, tells me. ‘For so long the trust has been so focused on restoring buildings – now’s the time we can be more outward looking, for the community to enjoy what we’ve saved.’

Both houses are free for members of Historic Houses to visit. This article was written for Historic House magazine, our official members’ magazine, which you can read online and in print as a member. Join today and start reading more articles like this, as well as exploring 300 of our houses for free and enjoying our live and recorded online lectures about our member houses.

Middleton Hall & Gardens

Middleton, Tamworth, Staffordshire, B78 2AE

Lamport Hall

Northampton, NN6 9HD